Senescence Uncovered: Worms Show the Way

Powerful model to study senescence

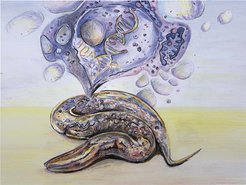

Senescent cells, which are damaged and inflammatory, contribute significantly to ageing. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing have found that worms can enter a senescent-like state, similar to that observed in mammals. This discovery provides a simple yet powerful model to study senescence at the whole organism level, enabling the identification of new ways to prevent or reverse senescence. These findings hold promise for developing therapies targeting age-related conditions and cancer dormancy.

To the point:

- Similar to mammals: Worms can enter a senescent-like state

- New model for senescence: Simple yet powerful model to study senescence at the whole organism level

- Basis for research into new treatment methods: Age-related diseases and dormant cancer

The researchers induced the senescent-like state in worms by manipulating the transcription factor TFEB. Under normal conditions, worms subjected to long-term fasting followed by refeeding regenerate and appear rejuvenated. However, in the absence of TFEB, the worm’s stem cells fail to recover from the fasting period and instead enter a senescent-like state. This state is characterised by markers such as DNA damage, nucleolus expansion, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the expression of inflammatory markers, which are similar to those observed in mammalian senescence.

‘We present a model for studying senescence at the level of the entire organism. It provides a tool to explore how senescence can be triggered and overcome,’ explains Adam Antebi, head of the study and director at the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing.

The TFEB-growth factor axis

TFEB is a transcription factor involved in cellular responses to nutrient availability. It plays a crucial role in responding to fasting by regulating gene expression. In its absence, worms attempt to initiate growth programmes without sufficient nutrients, leading to senescence.

’With our new model, we conducted genetic screens to identify mutations that can circumvent senescence. We identified growth factors, including insulin and transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta), as the key signaling molecules that are dysregulated upon TFEB loss,’ Antebi explains.

The TFEB-TGFbeta signaling axis is also regulated during cancer diapause, a state in which cancer cells remain in a dormant, non-dividing condition to survive chemotherapy. In the future, the researchers want to test whether their worm model can be used to find new treatments targeting senescent cells during aging as well as cancer dormancy.